Which is Better: Polyphasic Sleep, Biphasic Sleep, or Monophasic Sleep?

Sleep occupies roughly a third of our 24-hour lives. Add a regular 9-5 job, and that leaves only 8 hours for everything else. If you feel lucky enough to catch an episode of your favorite TV series, you’re not alone. The pattern gets old, but we cannot avoid cooking dinner, cleaning the house, putting the kids to bed, washing, drying, and folding the laundry. Sleep seems to be getting in the way, so why not look for a way out?

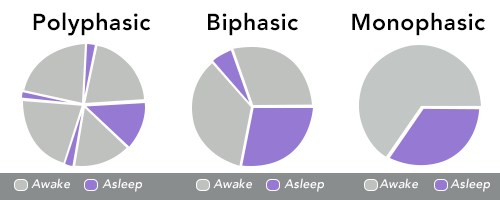

But sleep is just as consequential: It aids in our level of concentration, our immunity to illness, and our general outlook on life. If the pattern can’t change, then how can we sleep more efficiently? This article explores biphasic and polyphasic sleep as alternatives to the monophasic pattern. We investigate where these alternatives originate and whether they are justified by science. No matter the sleeper, our patented SleepPhones® headphones can boost your creativity, productivity, or rest. Read more below.

Controversy Between Monophasic and Biphasic Sleep

The standard recommendation for 7–9 hours of uninterrupted sleep each night describes human monophasic sleep, meaning “one phase.” All major health agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, follow this guideline. Although it is common for people to wake up in the middle of the night, these periods are often so brief that you might not notice. However, sleep disruption becomes a problem only if it takes you more than a few minutes to go back to sleep or if you slept 7–9 hours yet still feel groggy. Prolonged, distressing periods of disrupted sleep would fit the criteria for insomnia.

Evidence of biphasic sleep in humans has long contested the monophasic norm. In 2005, Virginia Tech history professor A. Roger Ekirch published his book At Day's Close, which describes over 500 historical accounts of first and second sleep. Traditionally, people would go to sleep a few hours after dusk, wake up around midnight, remain active for a few hours, and then go back to bed. Why? He claims that between the 17th and 18th centuries, street lighting became widespread. With even more people feeling safe after dark, spending time out at night likewise became popular—for both the nobility and the commoners.

What changed? According to Ekrich, the industrial revolution pressured people to become more efficient with their time and labor. Changes in the economy placed even more importance on shift work, meaning that people now had to dictate their lives by a strict sleep-wake schedule. Eventually, references to first and second sleep diminished, replaced with the term sleep maintenance insomnia. So, in the logic of biphasic sleep, insomnia is not so much a medical condition as it is a result of human beings’ natural tendency towards segmented sleep—a tendency now restricted by modernity.

As Ekrich’s argument goes, our culture is so heavily dominated by monophasic sleep guidelines that it's hard to think of insomnia as anything but a serious health complaint. Plus, to live in a global economy, more and more people are required to work and travel across time zones. Science writer Leon Kreitzman calls this “the 24-hour society,” a culture obsessed with colonizing the night and utilizing the hours we lose through sleep. Unfortunately, this leads to greater circadian rhythm disruptions, including sleep latency, early rising, and jet lag. So, are humans truly biphasic sleepers? And if so, what are we to do?

We’ll discuss the criticisms of biphasic sleep in a later section. For now, let’s talk about biphasic sleep’s cousin, polyphasic sleep.

Problems with the Polyphasic Sleep Trend

Many animals receive their daily sleep requirements through continual naps and are thus polyphasic sleepers. Cats, for instance, need 12–13 hours of sleep each day, but they reach this number by napping in periods of roughly more than an hour. Infants, toddlers, and preschoolers are also polyphasic sleepers: They need anywhere from 10–16 hours of sleep each day with naps included. Children require less sleep and will nap less often as they grow older, typically by the time they reach grade school.

But for adults, polyphasic sleeping is a health fad. Some people claim that geniuses like Leonardo da Vinci, Nikola Tesla, and Thomas Edison learned how to maximize their productivity by taking micro naps throughout the day. A 1943 TIME article describes how Richard Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome, slept for only 2 hours a day by napping for 30 minutes every 6 hours. He claimed that in doing so, his secondary energy would take over after his primary energy had been depleted.

Today, proponents of polyphasic sleep exist in a niche online hub. On their website, the Polyphasic Sleep Community lists eight different types of polyphasic sleep, with over 20 different subtypes. For instance, the community derives two of their most well-known subtypes—the Dymaxion and the Uberman—from Fuller’s extreme sleep schedule. For the more faint-of-heart polyphasic sleeper, the community provides five Everyman alternatives ranging from 3–6 total hours of sleep each day. These include one anchor period of sleep at night followed by 20 minute naps throughout the day.

If polyphasic sleep sounds risky, then you’d be right. In fact, the National Sleep Foundation’s consensus panel unanimously advises against polyphasic sleep. For one, the panel found a mere 22 studies on polyphasic sleep from 1935 to 2020, demonstrating an overall lack of scientific investigation. Despite what proponents claim, the findings of these studies do not at all suggest improvements to sleep quality, memory, mood, performance, and health. The opposite is true: participants showed more latent and fragmented sleep; worse recall and motor control; and greater depression, irritability, and emotional discomfort. What’s more, sleep deprived participants have been shown to underestimate their level of impairment, leading to even greater chances of mistake.

If polyphasic sleep is so bad, how does science account for people like Fuller? For now, it can’t. Because 7–9 hours of sleep helps the average adult function, this is what health organizations recommend. Although it is likely that a few people can function with much less sleep, the fact that there are only a few means that polyphasic sleep cannot be medically standardized. Plus, it is unlikely for scientists to continue studying polyphasic sleep, given the ethical consequences. So, we may never be able to explain the conditions for effective polyphasic sleep. If you still would like to try it out, please do so cautiously.

Scientific Disagreement with Biphasic Sleep

Given the lack of flattering evidence for polyphasic sleep, let’s return to the other two patterns. So, between monophasic and biphasic sleep, which is better for us?

That’s hard to say. Scientists are more concerned about which one represents the default state of human sleep patterns. Ekrich often cites Thomas Wehr’s 1992 study as having laid the groundwork for thinking that human sleep is biphasic. In it, 7 participants remained in their bedrooms for 14 hours every night for four weeks. At the end, Wehr discovered that participants’ average sleep extended to 11 hours a night, with about three hours of wakefulness in-between.

In responding to Ekrich’s criticism of his 2020 study, however, historian Gerrit Verhoeven argues that Wehr did not create conditions like those in pre-industrial Europe. For instance, the participants could not engage in any activity other than sleep while they were in the bedroom. Also, unless you lived far north during the winter, you would not have been exposed to such long periods of darkness. These limitations mean that the study on its own cannot be generalized to a whole population.

Verhoeven’s own analysis of 378 criminal court records in Antwerp, Belgium, found few references to biphasic sleep patterns. Instead, court reports—which, by nature, require precise estimates—suggest that the average person slept less than 7.15 hours each night. Additionally, only 86 of the reports mentioned nightly awakenings, with 87 percent of people reportedly waking up to street noise. Even when they did wake up, these people more than likely went right back to sleep.

Although Verhoeven’s study does not totally discount Ekrich’s hypothesis, the feud presents an interesting look at a current struggle within sleep science. Even a non-historical study in Current Biology, which followed three pre-industrial, hunter-gatherer societies in Africa and South America, found that sleep in these groups are more monophasic than they are biphasic. The study received positive editorials in the journal Nature and a later issue of Current Biology, but Ekrich disagreed with these findings too. We may not be close to discovering the “true” pattern of human sleep, but in the meantime, you can discover what sleep works best for you.

The Best Sleep for You, Thanks to SleepPhones®

If anything, the discussion of polyphasic, biphasic, and monophasic sleep reveals that the conditions for sleep are far more complex than we might at first realize. Of course, health agencies can rightly say that 7–9 hours, with maybe an hour more or fewer, has proven better for most people. But the duration, quality, time of day, length, and environment depend on other factors such as stress, work schedules, weather, time of year, indoor temperature, or even personal preference. Although having a standard helps us know if we’re being healthy, this standard becomes unhealthy if it's treated as a goal by which we measure our lives.

Some people swear by the power of the proverbial midnight oil. In her article "Broken Sleep," writer Karen Emslie personally identifies with Ekirch’s work. She takes comfort in the idea that her segmented sleep may not be the sign of some disorder. However, she mourns the loss of creative thoughts that can only come through nightly awakenings. It is Emslie’s final hope that the digital revolution will be more sympathetic to us than the industrial revolution. Specifically, she hopes that new technologies will allow perpetual night owls to remain in this creative space without the pressures of daylight.

SleepPhones® headphones help you discover that creative space. With our Bluetooth® and corded models, you can listen to TV shows, podcasts, audiobooks, music, and more. Slide out of bed, slip into our comfortable headband, and get to work! No matter if you’re painting, writing, crafting, or drawing, our proprietary SheepCloud™ fabric will keep you warm while maintaining breathability and durability. If your artistic endeavors run wild, don’t worry about the mess—simply take the speakers out, and wash the headband. Batteries last 10–12 hours, which is more than enough time for you to create your next masterpiece. Shop our catalog here.

SleepPhones® headphones help monophasic sleepers too. Rest against your pillow with ease, barely noticing our flat speakers and Bluetooth® modules. Simply play your favorite audio track, lie down, and go right to sleep—no pills or sleep aids required. Looking for a track to play? Listen to our collection of CDs, free MP3s, or ASMR from our list of featured artists. And, while you’re at it, download our Sleep Sounds by AcousticSheep® app, and join us in helping everyone fall asleep more soundly. Give yourself the sleep you deserve. Shop our catalog here.

What a blessing SleepPhones® are. I wake in the night, roll over, slip the band over my head, find whatever best puts me to sleep … and bang, I'm out like a light. Thanks to your product I'm sleeping better and more consistently now than I have in a very long time. I can't remember the last time I took a sleeping pill. I simply do not head to bed any more without my little MP3 player and my SleepPhones®. … Thanks bunches.

Medication free!

We've created a chart which illustrates the difference between the biphasic sleep cycle, the uberman sleep cycle, the dymaxion sleep cycle, and the everyman sleep cycle.

Learn more about alternative sleep schedules at our "Polyphasic Sleep" resource page.